Whether it’s looking back at the tremendous advances that have been made in combatting disease, or examining the breakthrough ideas and solutions in development today, conversations about technology’s role in health care tend to be optimistic — and rightly so. We’ve seen a surplus of encouraging examples, from gene therapy tools that could transform our ability to treat and prevent a range of lethal conditions, to predictive models with the potential to improve palliative care.

But when it comes to IT in health care, optimism has been harder to come by. Case in point: the electronic health record (EHR) is one of the most widely used technological tools in health care and one of the most disliked by physicians.

Today, Stanford Medicine hosted a National Symposium on EHRs to explore how to change that dynamic and create a compelling vision for the future of EHRs.

The symposium convened leading minds in patient care, technology, design thinking, and public policy to discuss how EHRs can evolve to keep pace with technological transformations — like AI, digital health, and genomics — that are taking place across medicine today. It also explored the kind of personalized, predictive solutions that EHRs might be capable of a decade from now, and what must change to achieve that vision.

As part of the discussion today, I shared findings of a Stanford Medicine EHR survey, conducted by The Harris Poll, which asked more than 500 primary-care physicians (PCPs) about their views on electronic health records. As we work toward a vision of what EHRs could achieve tomorrow, it’s important to know where they stand today — what they’re doing well for those on the frontlines providing care, and the ways in which they should improve.

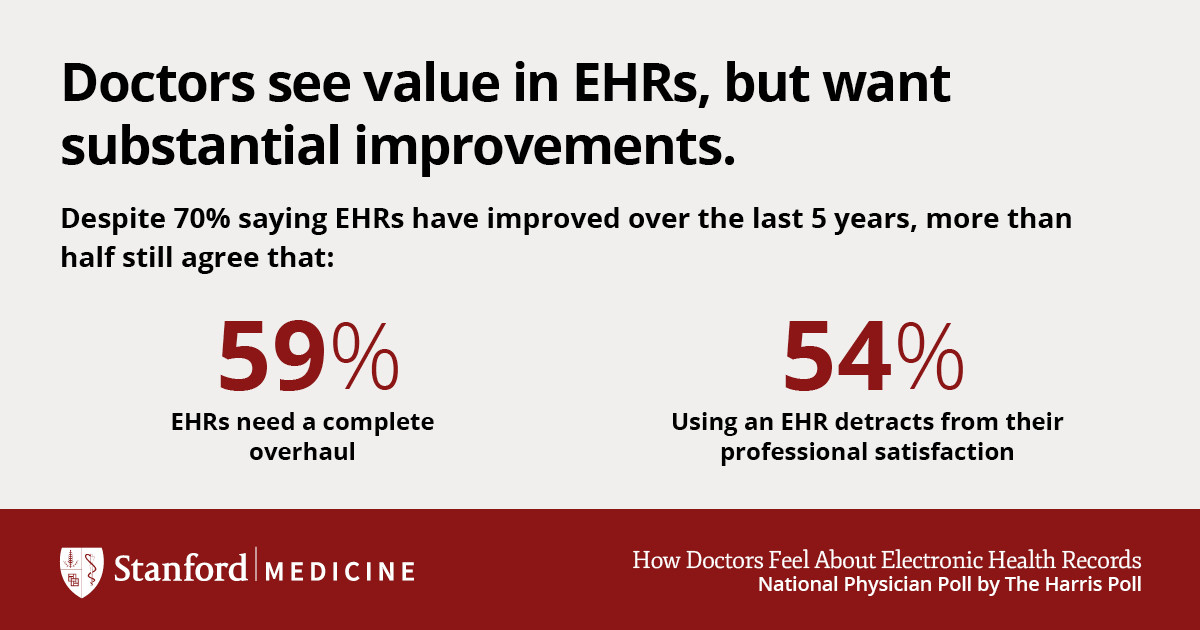

We found that roughly two out of three physicians believe that EHRs have generally led to improved care, yet four in ten believe there are more challenges than benefits with the technology.

A major source of these challenges is the time doctors must devote to EHRs. On average, physicians spend nearly half of each patient visit directing their attention toward EHRs. And this doesn’t include additional time physicians spend with their EHR after the patient has left. This may help explain why seven out of ten physicians (71%) agree that EHRs greatly contribute to physician burnout.

Another hurdle: EHRs aren’t living up to their potential as powerful tools that can aid in clinical diagnosis and treatment. Their primary value, according to physicians, is data storage (44%). Only 8% of PCPs say the main value of their EHR is clinically related.

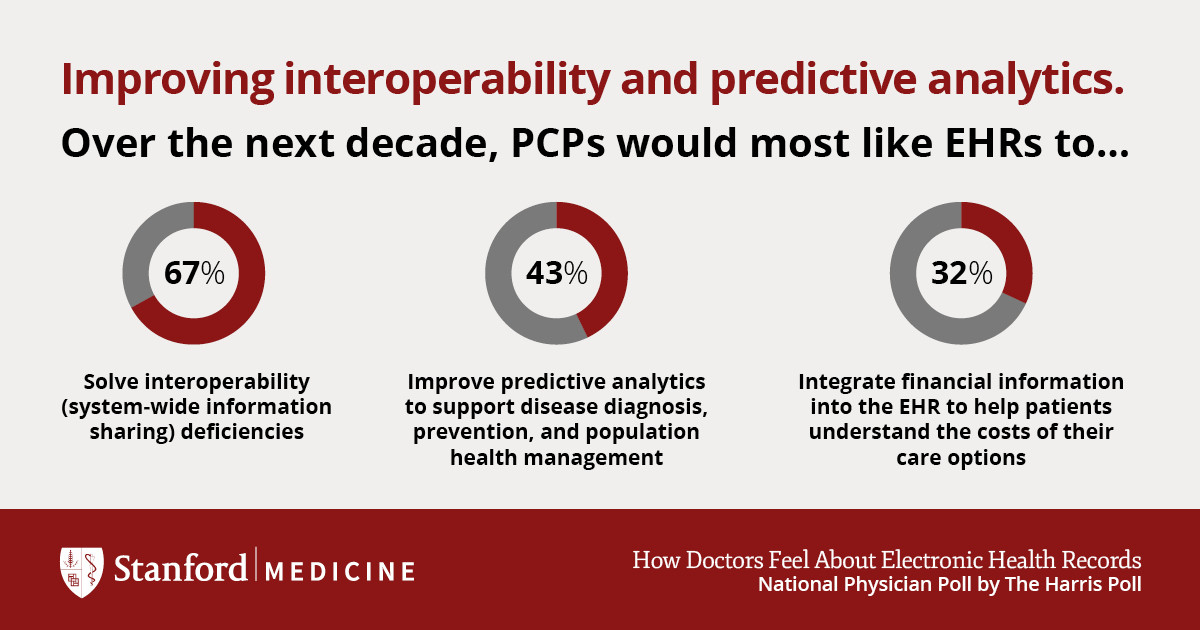

While the survey surfaced areas where EHRs are struggling, it also suggested concrete solutions going forward. Seven out of ten PCPs (67%) think solving interoperability deficiencies — being able to move or share your data across different EHR systems — should be the top priority in the next decade. Nearly half (43%) also want improved predictive analytics to support disease diagnosis, prevention, and population health management.

None of these are simple issues to address, and they clearly won’t be solved overnight or in isolation, but progress is possible. Today’s EHR National Symposium demonstrated that individuals across the industry are ready to collaborate on solutions and are eager to develop a compelling vision for the next decade. Clarifying this collective vision for EHRs and outlining steps to reaching it will be the focus of a white paper that Stanford Medicine intends to publish in the months ahead.

The good news is that we’re heading in the right direction: 70% of physicians from our poll believe EHRs have improved over the last five years. That’s progress we can build upon, and, over the next decade, help to accelerate.

#FutureofEHR